Comparison of the Indian and Chinese economy

China is the fastest-growing economy in the world and India is the second-fastest. Together they account for a disproportionate share of global GDP growth today. Both the countries are experiencing double-digit growth, resulting in millions of people moving from poverty to middle-class affluence in both the countries (Deloitte, 2006). Yet that is where the similarities end. Both these giants have followed entirely different paths to success, thus resulting in different footprints in the global economy. The world’s leading retailers have beaten a path to both China and India, although in India the process started later and with more formidable obstacles. Moreover, India’s cash-rich conglomerates are attempting to pre-empt the global giants by starting their own massive modern chains, to take advantage of the high growth and minimal competition (Deloitte, 2007).

GDP growth of China

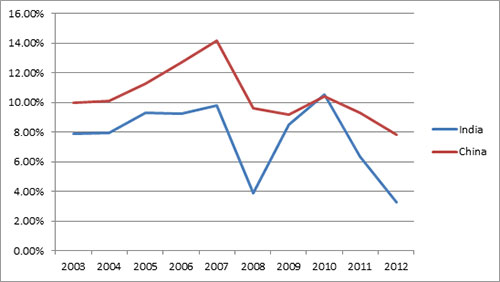

Over the last thirty years since the start of market-oriented reforms, China has successfully used inbound foreign direct investment (FDI) to expand its manufacturing and export capacity, which has further helped in accelerating the growth of its GDP. The share of the service sector in the GDP of China is 40% in 2012, while the share of manufacturing is reported to be 35% (Linklaters, 2010). Since 2000 China has consistently posted GDP growth figures exceeding the figures of developed economies and thus, shown exponential economic growth. However, China now faces a slowdown and raises significant macro-economic questions (Linklaters, 2010). As can be seen in Figure 1 below, the GDP growth rate increased from 10% in 2003 to 14.2% in 2007. But, the country reported a slump in 2008 with a growth rate of 9.6%. The figure further reduced to 7.8% in 2012.

GDP growth of India

The economic reforms of the 1990s jump-started the Indian economy with GDP growth rates accelerating to high single digits. India’s real GDP has grown over 7% annualized during the past decade, slumping down to 3.89% during the global economic downturn in 2008, gaining pace again at around 11% in 2010, as shown in the figure below. By real GDP, it is meant that the GDP figure has been adjusted for inflation. While the Chinese economy is manufacturing centric, the structure of the Indian economy is service-centric with around 60% of GDP being contributed by the services sector in 2012 (www.indiabudget.nic.in, 2012). The manufacturing share in GDP is around 15%. Agriculture’s contribution to GDP is around 14% (Goldman Sachs, 2010).

A comparison between Indian and Chinese exports

While China is seen as the place to produce or procure goods, India is the place to procure business and IT services. China’s export growth in terms of GDP shows consistency. As can be seen in Figure 2 below, exports in terms of GDP accounted for 29.56% in 2003 and remained at 27.33% in 2012. It should be noted that a sizable share of China’s manufacturing output and exports are produced by foreign-invested enterprises (McKinsey report, 2010). China churns out more manufacturing value-added than any country other than Germany, Japan, and the US (McKinsey report, 2010). China’s exports are now the third highest in the world (Deloitte, 2006). In order to keep its exports competitive, China has purchased the dollars entering China in order to prevent the Renminbi from rising in value (Deloitte, 2006). India shows a remarkable rise in its exports in terms of GDP, from 14.69% in 2003 to 23.83% in 2012. While China witnesses large migration of farmworkers to bigger cities to be employed in factories; the information technology service sector has absorbed India’s large population of educated English speakers and skilled workers by offering vast employment opportunities (Deloitte, 2007). The top export markets for India are UAE, USA, Singapore and China accounting for almost one-third of the total exports. The major export items include petroleum produce, gems and jewellery, transport equipment and machinery (EXIM Bank India, 2013).

A comparison of Chinese and Indian imports

Like exports, China is also one of the biggest importers and is one of the major emerging markets. The contribution of imports to the Chinese economy is found to be consistent over the years. As can be seen in Figure 3, China’s imports in terms of GDP were 27.36% in 2003 and 26.05% in 2011. China is the largest net importer of crude oil and other liquids in the world, with its net imports of petroleum and other liquids exceeding those of the United States (US Energy Information Administration, 2014). The rise in China’s net imports of petroleum and other liquids and rapidly rising Chinese petroleum demand is driven by steady economic growth (US Energy Information Administration, 2014). India’s imports as in terms of GDP have been increasing over the years, from 15.37% in 2003 to 31.54% in 2012 (as shown in Figure 3). Crude petroleum, gold and electronic goods constitute the major imports of India. The top import sources for India are China, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Switzerland and the USA, again accounting for one-third of total imports (EXIM Bank India, 2013).

Luring foreign investors

While India encourages entrepreneurial investment, China, much more than India, encourages foreign investment. The result is that, in 2012, China received $253 billion in foreign investment, while India received a mere $24 billion (World Bank data). Foreign investment in China’s retail sector is relatively free. This is because of the commitments that China made to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2004, upon joining. Chinese law today allows foreign retailers to operate without a partner in China. Open stores anywhere, and to source merchandise from foreign-owned local factories that, in the past, were obligated to export most of their output. The new rules enabled retailers to enter China without a massive investment for infrastructure developments (Deloitte, 2007). While China has grown rapidly through a high level of investment relative to GDP, India’s investment has been rather modest. Although the rules governing foreign direct investment in India have been substantially liberalized in recent years, the retail sector remains closed to foreign direct investment (Deloitte 2007). Foreigners may enter the Indian retailing only through franchising or wholesaling. However, single-brand retail trade was thrown open to foreign investment in January 2006 with an investment cap of 51% (Deloitte 2007). Thus, vertically integrated speciality chains can now directly invest in the Indian market. Despite the restrictions, some foreign retailers are starting to trickle into India.

Indian and Chinese economy head to head in the near future

The likelihood exists that both China and India will continue to grow rapidly and will continue to experience rapid retail modernization. Both markets are and will be attractive to the world’s major retailers and suppliers. Undoubtedly, India and China are bucking global trends.

China will probably see foreign retailers as the dominant players in their modern retailing. While in India there will be more of a mixture of foreign and local giants. Local conglomerates will create large chains, sometimes in partnership with foreigners, often without. The greatest risk to foreign investors in China will come from nationalistic government decisions. The greatest threat in India will come from a failure to accelerate the process of economic reform.

An issue concerning China’s economy today is the exchange rate of its currency, resulted from its efforts to keep its exports competitive. China has had to boost its own money supply, thereby creating a risk of consumer price inflation or asset price bubbles, resulting in an unsustainable situation. Thus, China will probably revalue its currency further, thereby increasing the purchasing power of its consumers. Growth will shift away from exports and foreign investment to consumer spending. Owing to an ageing population and rising affluence, consumer spending will grow more on services than goods. In India, the growth of consumer spending will be dominated by goods. Though both countries are likely to grow richer, India may still have to deal with the challenge of considerable poverty. This implies that China will become a market for discretionary and luxury goods and India’s focus will be on food and household products.

The revolution in IT-related service exports cannot fully account for the strong growth of India for long, as this sector is relatively small and India may lack sufficient educational resources to make it larger. To add to the misery, China’s government has decreed that all students must study English after the age of five (KPMG, 2013). This means that, within a generation, India’s advantage could be undone. Consequently, India’s future success may depend on its ability to shift toward strength in manufacturing. The good news is that India already possesses a big manufacturing strength. Yet sizable obstacles remain like poor infrastructure, insufficient investment to build new infrastructure, and regulations that create rigid ties in the labour market.

Reference

- Economic Survey 2012-13. Services sector. www.indiabudget.nic.in.

- Foreign direct investment. 2014. India brand equity foundation. http://www.ibef.org/economy/foreign-direct-investment.aspx Accessed on 2 May, 2014.

- Hiranandani, N., Rekhy, R. 2013. India calling: Inida-China business investment opportunities. KPMG report.

- Horn, J., Singer, V. Woetzel, J. 2010. A truer picture of China’s export machine. McKinsey Quarterly. September 2010.

- India’s International Trade and Investment. 2013. Export-Import Bank of India.

- India Revisited: White paper report. 2010. Goldman Sachs asset management.

- Jian, F., Malcolm, A., Pridmore, N., Thomson, K. 2010. Strategy and opportunity. China’s growth on the world stage. Linklaters LLP.

- Kalish, I. 2006. China and India: The reality beyond the hype. Deloitte Consumer business report.

- Kalish, I. 2007. China & India: Comparing the world’s hottest consumer markets. Deloitte Consumer Business Report.

- US energy information administration. 2014. http://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=15531 Accessed on 2 May, 2014.

- World Bank Data. 2013. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG Accessed on 2 May, 2014.

- World Bank Data. 2013. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS Accessed on 2 May, 2014.

- World Bank Data. 2013. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.IMP.GNFS.ZS Accessed on 2 May, 2014.

Discuss